What I Learned from a Life in Newspapers—and Why It Still Matters Today

Most of my career was spent in the newspaper business, and I remain proud of the work we did. I had the good fortune to be part of companies that, in my view, played a vital role in protecting our freedoms by upholding the values of a free press.

My first role was with Harte Hanks, where I had the privilege of working for Ed Harte and Dick Schlosberg (Richard T. Schlosberg III). Both men profoundly influenced my understanding of journalism’s purpose—and the essential truth that a truly free press must also be a profitable one. Without financial independence, journalism is vulnerable to undue influence from individuals or special interests.

That lesson was only reinforced later in my career by exceptional colleagues at Hearst, including Gene McDavid, Dick Johnson, Bob Danzig, George Irish, Steve Swartz, and Frank Bennack. These were people who believed that protecting the public's right to know also required business acumen and strategic clarity.

A profitable press doesn't mean chasing revenue for revenue's sake—it means cultivating a diverse set of customers and building multiple revenue streams. Unfortunately, many newspapers failed on this front. Instead of developing a clear strategy, they simply reacted to technological changes with a series of tactical responses. Innovation without strategy is like sailing without a compass—you might move quickly, but not in the right direction.

In the early 2000s, I had the honor of speaking at a conference hosted by Harvard Business School’s Clayton Christensen and investor George Gilder. I had met Clayton during a visit to Harvard and later invited him to speak with my leadership team at the Houston Chronicle about his theory of disruptive innovation.

Inspired by his work, we tried to evolve our approach. We looked for new ways to expand our reach, especially to households that couldn’t afford traditional subscriptions. We explored potential partnerships with fast-growing digital players like Craigslist—though, despite Craig Newmark’s willingness, we couldn’t find a model that worked for both sides.

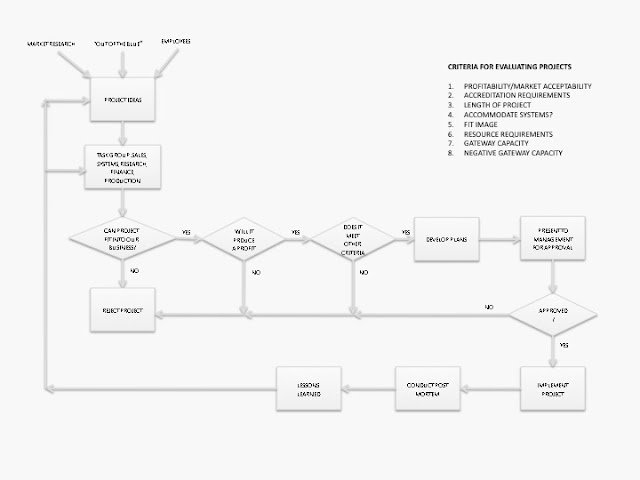

Looking back, I see now that many of our efforts—though well-intentioned—were tactical. We lacked a comprehensive strategy. It was only after several years of teaching at the University of Houston’s C.T. Bauer College of Business that I developed the MVOSSTE framework: Mission, Vision, Objectives, Situational Analysis, Strategy, Tactics, and Execution.

What makes MVOSSTE different is that strategy doesn’t begin until after you've done the hard work of identifying your customer’s needs and doing the research to understand them. Only then can you build a plan that aligns strategy, tactics, and execution.

So when people ask what newspapers should do today, my answer isn’t “embrace new technology.” My answer is: understand the jobs your readers need you to do. Build your strategy around those jobs. Then—and only then—should you determine which technologies and tactics will get you there.

Newspapers don’t need a new tool. They need a new mindset.

Comments